The opioid epidemic continues to harm individuals and communities worldwide; over-prescribing, overuse, and related overdose deaths persist in the United States and abroad. Without proper intervention, the proliferation of opioid use disorder and its negative impact on population health will continue. Healthcare professionals and stakeholders eager to stem this crisis are investing in the development and iteration of interventions that improve control of opioid distribution. As part of this effort, one team of healthcare researchers recently published a paper in Urology investigating the impact of an insurance payer’s novel opioid reduction intervention on the adoption of opioid-sparing pathways.

The authors of this publication, including lead author Dr. Catherine S. Nam, M.D., and her colleagues from Michigan Medicine, sought to compare the percentage of patients who filled peri-procedural opioid prescriptions before and after Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (BCBSM) launched a modifier 22 incentive for opioid-sparing vasectomies in Michigan. This program incentivized the utilization of an opioid-sparing post-operative pathway developed by the Michigan Opioid Prescribing Engagement Network (OPEN) by allowing the use of the modifier 22 reimbursement code for vasectomies performed with minimal or no post-operative opioids. Previous literature has demonstrated success in this approach for other medical procedures. The use of modifier 22 as an opioid reduction intervention was first launched by BCBSM in 2018 for select procedures and was expanded to include vasectomies in 2019. Typically, modifier 22 can be applied to select insurance claims with the primary procedure code when the work attributed to that procedure or medical intervention exceeds the typical amount of required labor. When approved, insurance companies may provide additional reimbursements of up to 35%.

The expanded eligibility for the modifier 22 into vasectomy presented substantial quality improvement potential given both how commonly this procedure is performed—approximately half a million times annually across the US—and the fact that a 2019 survey indicated more than half of urologists prescribed opioids for patients receiving a vasectomy, even though the procedure can be completed without them. For a vasectomy procedure to qualify for the modifier 22 program, a surgeon must intend to follow an opioid-free peri-procedural course as well as provide additional counseling to patients about post-procedural pain expectations, proper opioid disposal, and non-opioid pain management strategies.

Given the novel quality incentive for opioid-sparing pathway application to vasectomy with implications for payers, providers, patients, and policymakers, Dr. Nam and her colleagues were interested in evaluating the impact this policy change had within the state of Michigan.

To perform this analysis, Dr. Nam and colleagues leveraged Michigan Value Collaborative (MVC) administration claims data from beneficiaries in BCBSM’s preferred provider organization (PPO) plan. The data provided by MVC included men ages 20 to 64 who participated in urologic procedures between Feb. 1, 2018, and Nov. 16, 2020.

Between these dates, Dr. Nam and colleagues identified 4,559 men who underwent office-based vasectomies and 4,679 men in the control group, which consisted of men who underwent cystourethroscopies, prostate biopsies, circumcision, and transurethral destruction of prostate tissue. These procedures are all office-based and not eligible for opioid-sparing modifier 22, thus providing a point of comparison.

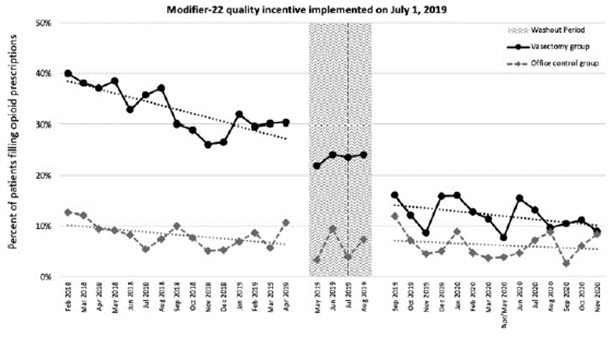

The results of the analysis demonstrated a strong association between the implementation of modifier 22 for vasectomies and filled opioid prescriptions. Before July 1, 2019—prior to the implementation of the expanded modifier 22 policy—32.5% of men filled an opioid prescription after receiving a vasectomy, whereas after implementation only 12.6% of men filled an opioid prescription post-procedure (see Figure 1). As highlighted in the figure below, Dr. Nam and colleagues found a 19.9% absolute reduction and 61% relative reduction in the percentage of vasectomy patients who filled peri-procedural opioid prescriptions.

Figure 1. Percent of Patients Filling Opioid Prescriptions Before and After Implementation of Modifier 22

Among the vasectomy patients in the analysis, for every three opioid prescriptions filled before the implementation of modifier 22, only one was filled after the initiative was implemented. They did not find a significant decrease in the percentage of patients who filled peri-procedural opioid prescriptions in the control group.

In addition to the decreased frequency of men filling peri-procedural opioid prescriptions for vasectomies, Dr. Nam and colleagues also found a significant decrease in the prescribed amount. After the implementation of modifier 22 for vasectomies, the oral morphine equivalents (OME) of peri-procedural opioid prescriptions fills dropped from 89.7 OME per prescription to 27.1 OME per prescription. Dr. Nam and colleagues estimated that this decrease in prescription size led to the distribution of approximately 8,473 fewer oxycodone 5mg pills in Michigan.

When asked about the significance of these findings, Dr. Nam explained, “This estimate helped us grasp the impact of the Modifier 22 policy change for patients as well as the community. If this was the impact in a bit over a year for a single procedure in one state, how large could this impact be annually? What could the impact be when quality incentive is expanded to additional procedures? What if the quality incentive could be expanded to other states?”

These findings suggest that the modifier 22 incentive does decrease the percentage of patients who fill peri-procedural prescriptions after a vasectomy and its implementation correlates with a reduction in the number of opioids circulating within the community. In addition to reducing the unnecessary presence of opioids in communities, this initiative also emphasizes a shift to refocus healthcare interactions on the patient. The required additional education about pain management and proper use of pain management medications implemented as part of the modifier 22 initiative provides patients with a better understanding of their care and encourages physicians to consistently deliver high-value care.

Despite the significant findings of this study, a question remained. If these practice changes were initiated by incentivized modifier 22 interventions, what would happen if BCBSM terminated the incentive? Since the publication of Dr. Nam and colleagues’ original study, BCBSM terminated the financial incentive using modifier 22 for opioid-sparing vasectomies on Dec. 31, 2021. This termination provided the group with an opportunity to observe the long-term impact modifier 22 had on physician prescribing patterns and patient opioid use after the incentive was no longer in place.

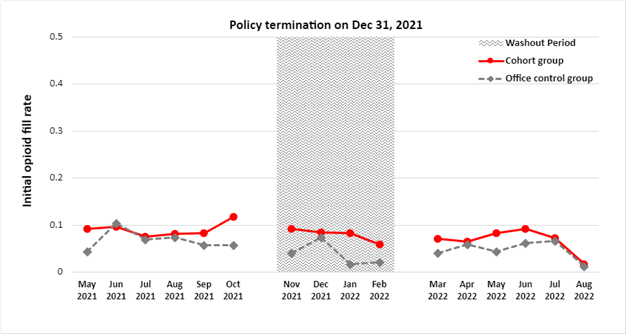

Dr. Nam and colleagues performed another interrupted time series analysis before and after the termination of modifier 22 using the same vasectomy and control groups. After analyzing the data provided by MVC, they observed no significant changes in the opioid fill rate compared to the rate observed when the modifier 22 program was in effect. This was true for both the vasectomy group and the control group (see Figure 2). The persistence of reduced opioid prescription sizes was also observed following termination of modifier 22. Prior to incentive termination, the mean opioid prescription amount was 59 OME, and after termination the mean further reduced to 36 OME.

Figure 2. Percent of Patients Filling Opioid Prescriptions Before and After Termination of Modifier 22

These critical findings demonstrate that physician opioid prescribing behavior remained constant after the removal of financial incentives. More research still needs to be done on the long-term impact of programs such as modifier 22; however, Dr. Nam and colleagues suggest that other payers could implement incentive programs like BCBSM’s modifier 22 initiative in order to spur similar changes in prescribing patterns and are hopeful that short-term financial incentives are part of the solution to creating lasting practice changes.

“This is the first example of a novel quality incentive targeting physicians to provide high-value care by incentivizing opioid-sparing pain pathway,” she said. “However, this incentive can be adapted to incentivize other high-value care – could we recognize physicians that are providing guideline-based care? How about ensuring that appropriate lab and imaging tests are ordered for patients as part of their care plan? And if so, could it be possible for there to be an investment made from the insurance companies to champion high-value care for a short period of time to have lasting effects?”

MVC is committed to using data to improve the health of Michigan through sustainable, high-value healthcare. Therefore, one of MVC’s core strategic priorities is intentional partnerships with fellow Collaborative Quality Initiatives (CQIs) and quality improvement collaborators. In partnering with clinical, administrative, and CQI experts to leverage MVC data for analyses, MVC aims to identify best practices and innovative interventions that help all members improve the quality and cost of care.

Publication Authors

Catherine S. Nam, MD; Yen-Ling Lai, MSPH, MS; Hsou Mei Hu, PhD, MBA, MHS; Arvin K. George, MD; Susan Linsell, MHSA; Stephanie Ferrante; Chad M. Brummett, MD; Jennifer F. Waljee, MD; James M. Dupree, MD, MPH

Full Citation

Nam, C. S., Lai, Y.-L., Hu, H. M., George, A. K., Linsell, S., Ferrante, S., Brummett, C. M., Waljee, J. F., & Dupree, J. M. (2022). Less is more: Fulfillment of opioid prescriptions before and after implementation of a modifier 22 based quality incentive for opioid-free vasectomies. Urology, 171, 103–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2022.09.023.