Surgery in the United States is transforming, with as many as 70% of surgeries currently performed in an outpatient setting. Ambulatory Surgical Centers (ASCs) have grown significantly over the past decade and are now a critical part of the healthcare system. The Ambulatory Surgery Center Association now represents more than 6,000 centers across the United States. ASCs account for more than half of the outpatient surgery market with roughly 23 million procedures per year. The growth of these centers has had a significant impact on hospitals. As the number of ASCs has grown and hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) have taken on fewer cases, many hospitals have elected to set up ASCs as part of their business.

This growth has been driven in part by greater scheduling flexibility and lower costs. Since most surgeries performed in outpatient settings are elective, patients are enabled to “shop” for their facility of choice prior to treatment. ASCs exclusively provide same-day surgical services that do not exceed 24 hours or require hospitalization. They are often – but not always – specialty-specific. Some of the most common specialties serviced by ASCs are orthopedics, pain, and ophthalmology (see Figure 1).

A recent study of Medicare patients evaluated the scope of practice, number of patients treated, number of procedures, and revenue for ASCs. The study found that across the United States there was a 7% increase in the number of ASCs certified to service Medicare patients. In 2018 there was an 11% increase in the number of services performed and a 6.5% increase in patients. The median number of surgeries performed at each ASC was 1,050 per year. Payments collected rose from $3.6 billion in 2012 to $5.1 billion in 2018, with cataract surgery accounting for 24% of all payments. The study concluded that the increased revenue was most likely due to the increasing complexity of procedures being performed and, thus, higher reimbursement.

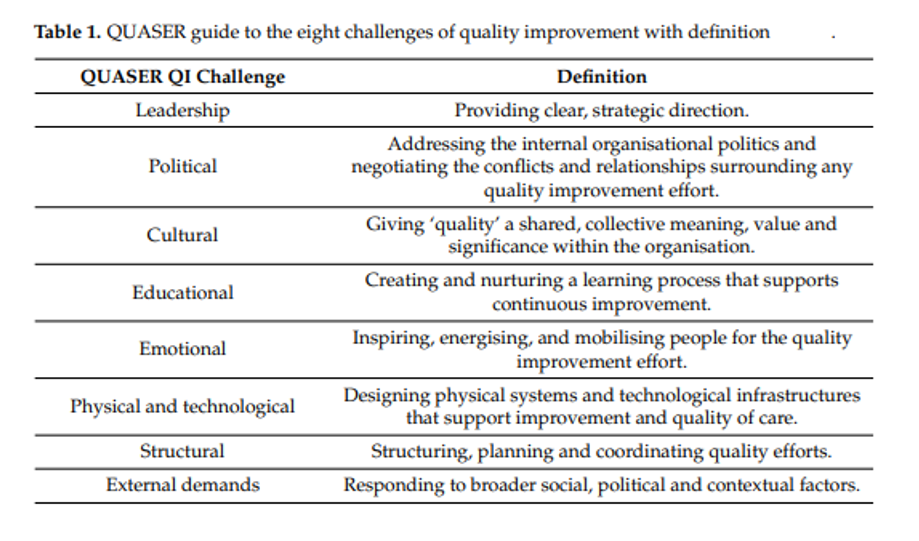

The increase in more complex surgeries at ASCs can most likely be attributed to better anesthesiology methods that allow for improved pain control and reduced post-operative recovery time, as well as new technologies and techniques that make surgeries safer and more comfortable. The Leapfrog Group identified over 50 different procedures performed across 10 disciplines in their 2022 ASC outpatient surgery fact sheet (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

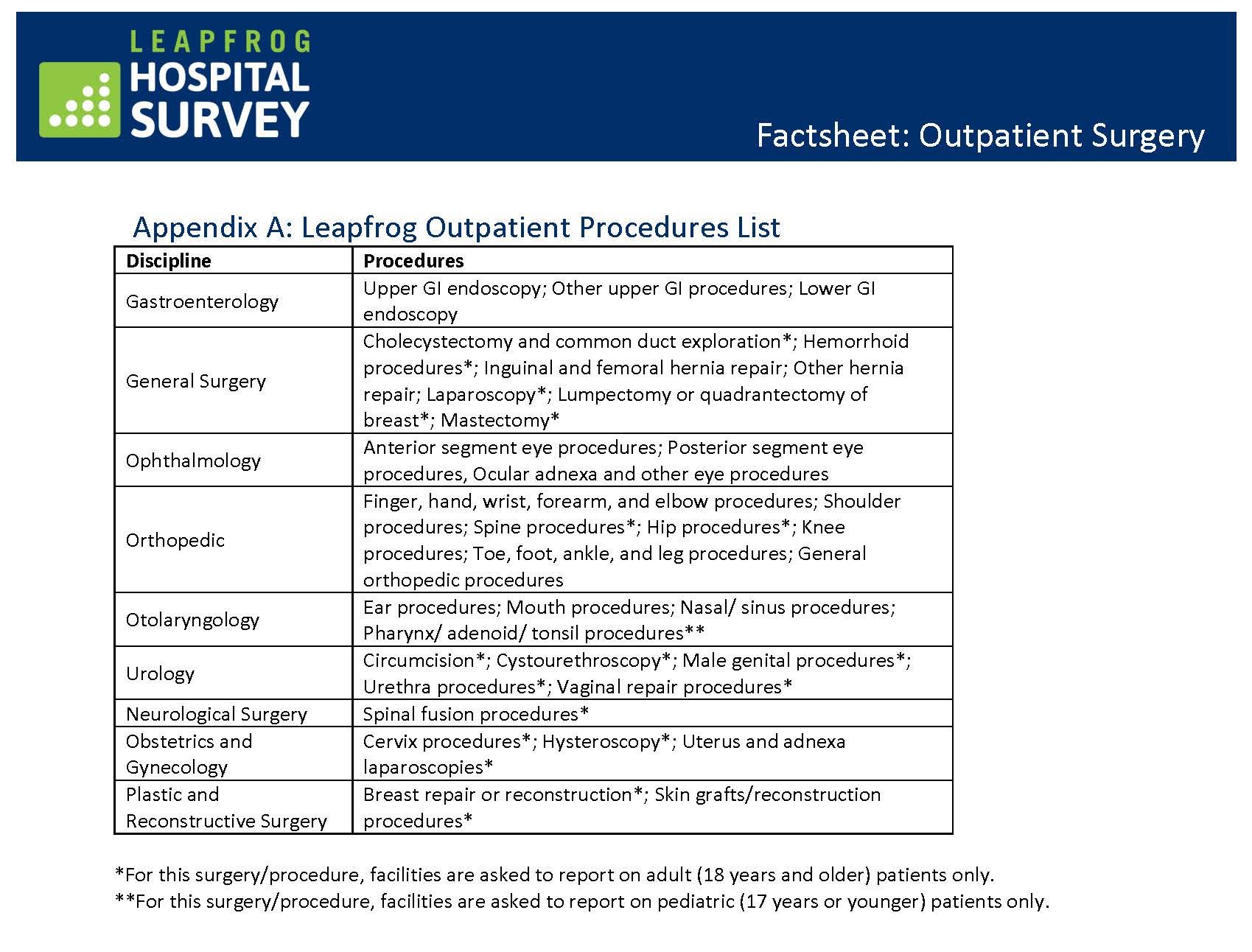

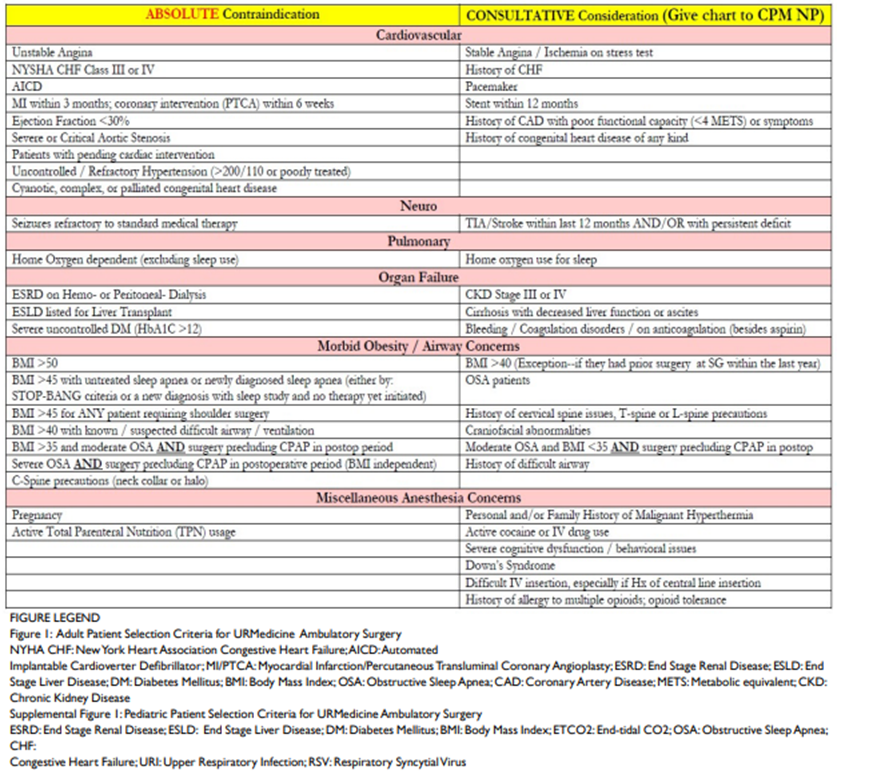

Associated with this rise in complexity is the need for ASC staff to accurately identify high-risk patients who are not appropriate candidates for ASCs. Many ASCs have created their own methods for identifying these high-risk candidates since there are no universal or ready-to-use published criteria. Although no preoperative screening system is perfect, the average national ASC transfer rate to an inpatient facility is just 0.42%, and in one study the use of a criteria checklist (see Figure 3) helped the facility achieve a 0.17% transfer rate.

Figure 3.

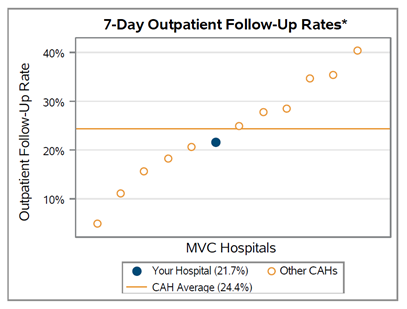

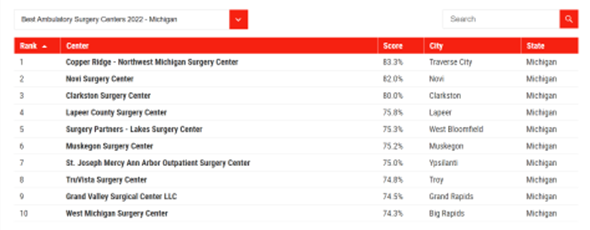

To assist the growing number of patients in their selection of a surgical provider, several organizations now publish evaluations about the quality and safety of various ASC facilities. For example, Newsweek published their rankings of "America's Best Ambulatory Surgical Centers" earlier this year in partnership with the global research firm Statista. The list spotlights 470 facilities in the 25 states with the most ASCs, with up to 10 ranked centers by state. Michigan's highlighted ASCs (see Figure 4) received scores of 74% - 83%, which was based on a "reputation score" and KPI data score.

Figure 4.

As ASCs continue to have a transformative impact on the surgery market, the Michigan Value Collaborative is interested in learning more about the metrics and data being utilized by these stand-alone or hospital-affiliated centers. If you have any information to share, please reach out to the MVC Coordinating Center at michiganvaluecollaborative@gmail.com.