The past 18 months of the pandemic forced healthcare to be creative and responsive to the needs of the moment, and in that time the MVC Coordinating Center heard from members about how they are working to maintain a high quality of care. The challenges and pivots shared by members vary significantly because facilities were impacted at different points in time and with varying levels of severity. However, one challenge echoes loudly and consistently for hospitals big, small, urban, or rural: the staffing shortage. This problem isn’t specific to Michigan. Across the United States, hospitals don’t have enough staff to keep up with their normal standards of care, with many having to turn away patients and ration care.

Health professionals are the lifeblood of healthcare delivery, so attaining or maintaining a high quality of care is only achievable with appropriate staffing levels. The Institute of Medicine framework defines quality care with six aims: that it be safe, effective, patient-centered, timely, efficient, and equitable. Some of those aims have been directly exacerbated by the pandemic—such as health equity or safety—while many have been at least indirectly impeded by the strains on frontline workers.

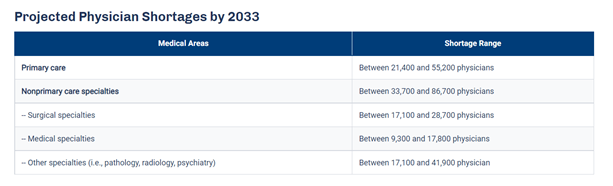

An article published by the Detroit Free Press this month titled, “Michigan hospital staffing shortage nears crisis point as COVID-19 patients rise,” paints the current situation as dire. The article quotes Brian Peters, the CEO of the Michigan Health & Hospital Association, as saying, “I have never heard a consistent theme from across our entire membership like I have on this staffing issue." He adds that the shortage affects multiple sectors of the workforce, such as nurses, physicians, housekeeping, technicians, and food service personnel. These new staffing issues occur within an industry that was already concerned about an expected shortage of primary care physicians (PCPs). The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) published data that predicts an estimated shortage of between 21,400 and 55,200 PCPs by 2033 (see Figure 1), in part due to a population that continues to grow and age.

Figure 1.

Some hospitals suggest burnout as the main culprit for the current staffing shortages. A literature review on the effect of burnout on quality of care defines burnout as a state of fatigue and frustration manifested as physical and emotional exhaustion characterized by dissatisfaction and stress, with symptoms such as, “physical fatigue, cognitive weariness, and emotional exhaustion.” Anyone in that condition cannot perform at their best. So as quality teams try to find treatment efficiencies for conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or congestive heart failure (CHF), the elephant in the room is that they may not be able to provide treatment if nurses, technicians, and physicians aren’t adequately staffed.

The industry is expecting the shortages to increase slightly in the coming weeks as vaccination mandate deadlines approach. Currently, those health systems requiring COVID-19 vaccination include Henry Ford, Michigan Medicine, Beaumont Health, Trinity Health, Spectrum Health, OSF HealthCare, Ascension Health, and Bronson Healthcare, along with Veterans Health Administration facilities.

A variety of strategies are being proposed to lessen the burden felt by the shortage. Since it takes time to recruit new people into medical fields, these approaches generally fall into one of two categories: 1) retain current staff, and 2) deploy current staff as efficiently as possible.

The approaches that hospitals have mentioned for retaining staff are short-term in nature, ranging from approval of overtime and bonuses to instituting new staff well-being programs and sharing mental health resources. Efficient staffing is a more complex approach, but long-term with the potential to reduce the expected burden from future PCP shortages. The Harvard Business Review published an article that outlines strategies for efficient staffing in response to the PCP shortage, which could be repurposed and applied to other healthcare workforces. Among their suggestions, they highlight Advisory Board research that proposes the threefold answer is, “better use of PCPs targeted at specific populations, greater use of non-physician labor where appropriate, and much broader deployment of technology to increase access to primary care.” These suggestions align with several other priorities often voiced to the MVC Coordinating Center by members, including equitable access to care, expanded telehealth offerings, and improved care coordination utilizing nurse practitioners and physician assistants.

The work ahead will be challenging, as it often is in healthcare. Hospitals will continue to shoulder a shared burden in the months ahead. MVC encourages all members and partners to share resources that may help a peer institution improve the quality of care for Michigan residents. Please continue to bring these ideas to future workgroups and networking events, and contact the MVC Coordinating Center at michiganvaluecollaborative@gmail.com.