For several years, patient-reported outcomes (PROs) have been a topic of interest, in part due to increased utilization of electronic data and the integration of delivery systems. PROs are defined by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and National Quality Forum as "any report of the status of a patient's health condition that comes directly from the patient, without interpretation of the patient's response by a clinician or anyone else." In short, PRO tools ask patients questions to measure how they feel and what they are experiencing. With patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), patients provide information about their health, quality of life, and functional status, either in absolute terms (e.g., pain severity rating) or in response to treatment changes (e.g., new nausea onset). The goal of gathering this information from the patient’s perspective without any interpretation from a healthcare provider is to improve both the quality of care being delivered and health outcomes.

The use of PROs has a variety of potential benefits. They can elicit enhanced patient engagement, be used to clarify the patient’s priorities and thus improve shared decision-making between patients and providers, and can bring to light any benefits or harms of interventions. The potential impact of PROs, therefore, is substantial because involving patients in their healthcare is linked to a myriad of positive patient outcomes. For example, based on a review of studies investigating patient participation, some of the benefits to patients include:

- increased satisfaction and trust,

- empowerment,

- greater self-efficacy to manage health,

- higher quality of life,

- better understanding of condition and personal requirements,

- improved adherence to medical treatment plans,

- improved communication about symptoms with positive and lasting effects on health.

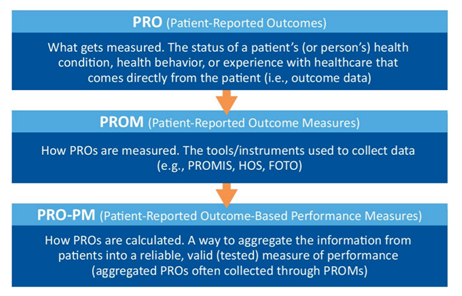

Ever increasing in its availability, the use of PROs is included in clinical investigations, healthcare practice, healthcare management, and various regulatory or reimbursement areas. As the patient continues to become more central to healthcare, they are in the best position to determine if their healthcare objectives have been achieved. PROMs are not the same as measures reported by patients on their experience of the healthcare system, such as being treated with dignity or waiting too long; however, patient-reported outcome-based performance measures (PRO-PMs) are beginning to find their way into healthcare and may integrate such measures. To help understand the relationship between PROs, PROMs, and PRO-PMs, see Figure 1, which was designed by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in their supplemental guide on PROMs.

Figure 1.

To gather PROs, the tools and instruments known as PROMs must measure criteria that are identifiable, valid, and reliable. Most often these are general or disease-specific self-completed questionnaires, scales, or single-item measures that provide a score for any of the following:

- functional status,

- health related quality of life,

- symptom and/or symptom burden,

- personal experience of care,

- health-related behaviors.

Generic PROMs often delve into areas covered by a variety of different conditions, allowing for comparisons across multiple medical conditions. These PROMs help with evaluation and implementation of care provision methodology and equality of service delivery. Some may even provide a cost-effectiveness component. Disease-specific PROMs identify the impact of definitive symptoms on the condition. PROMs can be used as either the primary or secondary outcome measure of a study or trial, and most studies use a combination of disease-specific and generic PROMs.

Measurement tools integrate other existing data (biological, genetic, clinical, and physical) to assess how a patient is functioning regarding their overall health, quality of life, mental well-being, or satisfaction with a healthcare process. Using all these data sources provides a more complete picture of the patient’s health journey and allows for patients and their providers to share decision-making and define individualized care. They also provide a unique opportunity to identify inequalities in healthcare access and treatment.

When utilizing PROMs, practitioners must plan for how the information will be collected and utilized. PROMs can be collected in a variety of ways, including face-to-face interviews, online or paper questionnaires, telephone interviews, or diaries. When deciding which PROMs to utilize, it is important to consider the preferences of patients, providers, and any other involved decision-makers. It is also essential to consider the cognitive, physical, demographic, and socioeconomic barriers that may exist for the patient to ensure they have adequate accommodations to participate. The length, schedule, and timeframe of assessments should also be appropriately assessed, along with any permissions needed to use the information. Lastly, the PROMs should be easy to score and interpret, actionable, and able to facilitate clinical decisions.

The use of PROs is here to stay. The hope is that improvements in interoperability, data governance, security, privacy, and ethics will allow greater integration of PROs. In turn, PROs will allow patient preferences, needs, and health outcomes to further drive value-based healthcare.